It’s been a couple months since I finished my hike to all the pubs in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. I’m now back home in hot hot Arizona, reflecting on my 350 mile, four-week walk. I hiked to 89 pubs (a number that does not include the score of pubs visited in the towns just outside the bounds of the national park). I’ve been trying to work out which variables make a great country pub. Not such an easy task.

Over the last few years, I’ve hiked somewhere north of 3,000 miles in the UK. Every hike was planned with pubs in mind. For me a good walk is hiking and pubs in nearly equal measure. As a result, I’ve seen my fair share of country pubs. Not all of them are winners. Most are solid, and a scant few are exceptional.

But how do I measure the virtue of a country pub? Initially, I’d venture that a good country pub needs two essential ingredients: good beer and an atmosphere with some measure of bucolic aesthetic. Put these two factors together in almost any measure, I’m satisfied. But what makes a good solid country pub into exceptional territory? Great beer and/or great atmosphere? Yes, of course. But I think the true greatness variable is more difficult to measure than the other two. It’s about the people. People make a good pub great, even a mediocre pub great.

Warmth, friendliness, hospitality. A pub can’t be great without it. Just the name “public house” invokes this truth. It’s a place for community, everyone is welcome.

Every pub I’ve truly loved always involves meaningful interaction with people. When I walked from Land’s End to John O’ Groats, my favorite pub was a crossroads country pub in Somerset called the Halfway House (Pitney). The pub boasted an impressive array of well kept local craft forward real ales. I was absolutely tickled that they served the beer from a back room via gravity pours (which was the method employed before the advent of the bar (which was first introduced via Gin Palaces) and the beer engine). I asked the publican to pick beers for me, he happily and competently obliged. It was a wonderful experience.

When I think back to the Halfway House though, the first memory that comes back is not just of the beer. It’s of a group of locals that invited me to their table and one particular local that later took me out in his beat up vintage convertible that broke down when we went uphill. I had a beautiful evening of skittles and laughter while pushing a tiny broken convertible uphill. Good to great.

When I was trying to come up with ideas for a walk this summer, I really tried to muster interest in places I’ve never been: Wales, East Anglia, Cape Wrath. But my day dreams always come back to the Yorkshire Dales. I can’t quite put my finger on what draws me back there. A thought struck me that maybe I could hike to every pub in the park, which would also have the bonus effect of getting me to the small recesses I would otherwise never visit.

After a few days of furious googling and planning, I developed a workable meandering route. And then, just as suddenly as the idea came, I put the idea on the backburner while uncertainty raged due to covid. While I had a ticket on hold for months, it wasn’t until the day before I left that I decided to actually go through the trip. I finally revisited the hastily made route again while sitting in quarantine in Halifax. I opted to embrace the adventure and just go without more planning.

And so, it was after receiving my all clear to end quarantine at 9pm the night before that I found myself on the edge of the Yorkshire Dales National Park with a profound hangover, dubiously staring at a pint at the Elm Tree Inn in Embsay. With effort, I finished the first official pint and quickly found myself in the familiar grassy bucolic expanse of the Dales.

Fortunately, an older woman was navigating the footpath ahead of me. My head still aching and spinning, I was in no condition to figure out the apparently seldomly traversed trail myself.

A few hours later, I entered the well-manicured outskirts of Hetton, home to the famous Angel Inn and Hetton brewing, which brews a couple of beers I really like. As I approached the Angel Inn, it became apparent something was off. A slew of Porsches and Range Rovers sat conspicuously in the very clean (sterile?) facade of what was once the Angel Inn but now “The Angel At Hetton,” complete with large Michelin star plaque. I could feel the side glances as I approached. A minute later, I had been politely turned away from The Angel At Hetton, as beer was apparently reserved for guests of the establishment.

This blog is not the place to fully articulate my disdain for that recently “reimagined” pomp factory. It was no longer a pub. In fact, it had become the antithesis of a pub. I shook the dust off my feet, slightly relieved that the obligation of another queasily choked-down pint had been postponed.

Thusly, my hike began. Pubs came and went. A wedding at the Craven Arms in Appletreewick (one of my favorite pubs for years) brought a bus load of posh sounding Londoners who, after a few drinks, played a role in a night of a parade of pints of Old Peculiar from wooden casks and deep conversations. Earlier in the day, the relatively new publican up the road at the New Inn reluctantly showed me the cellar for his astonishing 14 beer engine rural pub. I still don’t know how he can go through that much beer.

It quickly became obvious that the covid staff shortages would result in a number of pubs with limited hours. So I came to terms with the fact that I would have to settle for a picture of a pub when I couldn’t get in. Fortunately, while this wasn’t an infrequent occurrence, there were only a couple pubs I was disappointed not to get into.

At the wonderful Fountaine Inn in Linton, I got into a conversation with the publican about all the other characters I was bound to encounter on the rest of my trip. I was impressed by the Fountaune’s house beer, a surprisingly flavorful amber. A day later, after enduring a deluge while in Grassington and being shushed by a grumpy English dickhead (who chose of all tables in a empty and caverness pub to sit next to me and another patron talking tables apart), I came back to a poorly pitched tent with a gallon of rain water in it. Fortunately, my friendly campsite neighbor, a sweet man with a pet baby ferret helped me get sorted enough to enjoy a dry night’s sleep.

One pub I was sad to not get into was the profoundly rural Thwaite Arms in Horsehouse. Later that night, I found myself gently informing the publicans of a fully booked pub that if they didn’t feed me, I’d go without for the night. In no time, I was presented with an enormous piping hot plate of sausage and mash. The rest of the night was a blur of pints of Hetton Dark Horse and hilarious banter between the husband and wife team behind the community owned Foresters Arms in Carlton in Coverdale. I pitched my tent in the 10pm dusk on the top of Melmerby Moor just as the rain started, full, tipsy and content. From a good pub to a great one.

The next day, I happened to catch an AM pint in the Fox and Hounds in West Witton on the very last day of a quarter century tenure of the husband and wife landlords. Between the conversations with the furniture movers, the soon to be retirees dolled out goodbye conversations with the locals.

I passed through Aysgath and shot up into Bishopsdale. At another Fox and Hounds (no relation) in West Burton, I had another curry meal at an unremarkable pub. Unremarkable except for the fact that the pub seemed a fixture of the community, as much as the village green where I watched kids play soccer over my curry and pints. Later that night at the Street Head Inn in Newbiggin, I reluctantly returned a pint that had turned (a pint that was bought for me by a couple that saw me and the last mentioned Fox and Hounds) and walked away with two complimentary fresh pints. Three pints for the price of none.

The next day I returned to Wharfdale. I had two pints in one of the loveliest places on earth: the George Inn in Hubberholme. The George Inn has a storied past. It was famously the favorite place of the author J.B. Priestly who described, and by extension the small pub at the George Inn, as “smallest, pleasantest place in the world.” I don’t disagree. The George Inn exudes all the tangible and intangible bucolic virtues of the perfect country pub. The jack russell “George” curled up on a victorian looking tufted footstool in front of the cast iron fire. The publican “Ed” with a quick wit, incredible memory and fastidious observances of the traditions that make the George special,i.e. a burning candle on the bar that used to indicate the local vicar was available. After alternating conversations with the affable landlord and a part time cricket umpire, full time history professor, I reluctantly shambled away from the fully booked inn to the next village.

My wife and I have a self explanatory tradition we call tequila Friday. It being Friday, I found myself in Starbotton at yet another Fox and Hounds (no relation) staring at a generously poured dram of Don Julio, which was a nice surprise as most tequila I find (especially in the countryside) is absolutely terrible. He seemed very proud when I told him that I was impressed with his tequila.

On Saturday, I had a couple pints and fun conversation at the wonderful Falcon Inn in Arncliffe, where I set off for a beautiful walk into Malham. I was disappointed with the two pubs in Malham, just before dark I walked a mile down to Malham Kirkby and had a great time with some locals at The Victoria.

From Malham, I hiked to depressing Long Preston and then to sleepy Settle, where I booked a hotel for a few nights. Settle is technically outside the bounds of the national park, which of course, didn’t stop me from going to all the pubs. I ended up at the Talbot Arms on multiple occasions. I intended to hike a circular route to Austick and Clapam from Settle without my backpack. I was having so much fun that I just kept going to Ingleton. In Ingleton, I had a pint and caught the bus back to Settle. It wasn’t until after the whole hike was over that I discovered that in my hasty planning I had missed at least one pub. While Ingleton is not in the bounds of the park, the area just outside is. The Marton Arms, less than a mile from where I picked up the bus, sits just inside the bounds of the park. Poor planning on my part.

After a rest day, I set off north. It was too early for lunch when I reached the Craven Heifer in Stainforth. I had a half pint of Thwaites IPA and then was convinced (I didn’t need much convincing) to have another by the publican. This was one pub I really wished I had hit at night. A couple of restored penny slot machines, a game room, dance floor disco lights tastefully tucked away, all set against handsome wood paneling. The banter of the young staff. The easy demeanor of the publican. I suspect this was a pub in which I could have an exceptionally fun night.

The hiking highlight of my trip occurred in Ribblesdale two days later. I chose a trail along the ridge of Park Fell. Snaking through limestone outcrops, I came into view of the peak of Ingleborough and Ribblehead Viaduct simultaneously. I’ve come close to the viaduct a few times but never actually seen it. Up close, the viaduct is thrilling, even with the 100s of parked cars of fellow tourists.

Although it was my second time to Dentdale, I was enchanted anew with the cobblestone streets and whitewashed buildings of Dent. The two pubs sit in view of each other, I assume, as they have for 100s years. There’s a supposed vampire in the graveyard, a still visible brass rod driven through the coffin assures me that he is securely asleep.

Through Barbondale, it rained and rained. I had a solid pint and delicious roast beef sandwich at the handsome and friendly Barbon Inn before setting off towards Kirby Lonsdale. It was during this stretch that I became aware of a fact that would affect my next few days: Appleby Horse Fair was about to start and the travellers were on their way. At first, I was smitten by the horse drawn caravans but soon, the more sinister aspects of groups of the travellers started to appear.

First, in Kirkby Lonsdale camping became an issue. The campsite I was headed towards closed, ostensibly to discourage travellers from trying to camp there. This forced me to a post covid pop up campsite at the rugby pitch, which charged an extortionate £25 for a rocky pitch with a locked porta potty. Normally, I would just wild camp but with Kirkby Lonsdale overrun with tourists and the travellers about, I didn’t feel comfortable. Nevertheless, I sat for a long time staring at Ruskin’s View and then managed a fun tequila Friday.

I took a couple days off in Kendal, the only place I could find an available hotel room. I met a friendly young local at Fell Brewing who let me sit with him at the otherwise fully booked bar. He took me to the heaving 18-20 year olds’ dance party pub where I smoked a couple cigars, anonymous and old in a throng of covid oblivious and horny young adults. I stumbled through the empty glistening streets just before 3am.

The campground in Sedbergh was full so I ended up at another post covid popup campground, this time with a view worth the price of admission. After a 5pm scramble to find a meal, I landed at the only pub with a table left. As I ate and drank, I watched as the pub turned away over 30 people in the ensuing hours.

I set off north along the alluring river Lune to Orton, an exceptionally friendly little village. I booked a £40 room at the George Hotel, checked in, changed and posted up at the bar. On its face, there’s nothing overly remarkable about the George Hotel. It boasts a handsome old coaching house exterior, a warm bar, wholesome food, mediocre beer. But it was one of the friendliest pubs on my walk. Not only were the husband and wife landlords sweet and attentive, the local farmers, older men, were a fucking hoot. They came in and one by one had little conversations with me in between friendly verbal jabs at each other. One local, a bit of an academic (besides showing off his new Cambridge greek tomes, there was peppering of “30 years” “cambridge” and “physics” in our conversation) saw me smoking a pipe outside and wanted to talk pipes. He invited me over to his table later and we talked pipes and language until closing time.

Crosby Ravensworth is 5 short miles from Orton. My timing was intentional. Having arrived in Orton on a Tuesday, I was really just waiting for the community owned Butcher’s Arms in Crosby Ravensworth (closed Monday and Tuesday) open on Wednesday. On my way out of Orton, I climbed up onto the moors to find the heather exploding with purple in the early throws of bloom. The path through the moors followed a gully flanked in every direction by violent plumes of violet. It felt like I was walking through a set of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

Unsurprisingly, I arrived in Crosby Ravensworth with time to spare. After arranging a pitch for the night, I set out into the rain to explore the village. The church in the village boasts three virtues: 1) the approach to the church, over a cobblestone bridge, through victorian cast iron gate, is absolutely breathtakingly beautiful, 2) the remnants of a medieval cross (the horizontal arms broken by Cromwell’s men) in the yard, and more practically in the cell signalless valley, 3) wifi.

I arrived at the Butcher’s Arms just as they opened at 5. I ate, retired to a recently installed outdoor covid awning to smoke and watch the rain. It wasn’t until nearly 10 that I decided to come inside. I sat up at the bar and was promptly engaged in conversation with the locals. After trading pints with a local farmer, I peppered the publican about the specific challenges of running a community owned pub. The Butcher’s Arms was only the 6th British pub to be saved by its community. Midnight, after 8 pints, I staggered back to my tent, overly drunk and content.

Not surprisingly, the 17 mile hike to Kirkby Stephen was unnecessarily difficult, made all the worse by the unexpected closure of the Three Greyhounds in Great Asby. Despite the locals blocking off nearly every open area, the travellers had taken over the village. Untethered, horses sauntered through the streets, gypsy horse drawn caravans gathered around open fires rigged with suspended cast iron cookware. I was really looking forward to a meal at the Greyhounds. I was running on fumes. As luck would have it, someone came out of the locked pub as I stood dumbly staring at closed notice. She was very apologetic and gave me a can of coke. Just what I needed to soldier on.

Kirkby Stepehen was near apocalyptic. All the good pubs were closed. The two that were open were only serving out of plastic cups. One pub had a sign in the window informing ne’er-do-wells that the pub was closed and no money or stock was on premises. I checked into my campsite and just about cried when I discovered the site had a food truck selling tacos that night.

The campsite was so wonderful that I decided I would try to stay two more nights. The next day, I ditched the backpack and headed out on a jaunty circular route. It was one of the few sunny days of the trip. I hiked the Coast to Coast years ago and, while on my way to Ravenstonedale, was pleasantly surprised when descended into a valley I instantly recognized as part of the C2C. Ravenstonedale was a delight. Much posher than your average Dales village, I lunched on crab risotto at the Black Swan and felt like a 19th century aristocrat returning from a fox hunt.

It was Friday, and I have my traditions and travellers were racing down the mostly shut high street in Kirkby Stephen. I took a hasty shot of tequila out of a plastic shot glass in a traveller packed pub, had a hard time finding a meal and decided it was time to put some distance between me and the Appleby Horse Fair.

I made 18 miles for Hawes the next morning. At the Moorcock Inn, after amusing myself with as many jokes as my hunger would permit, I inquired whether there were any vacancies. There were not, which was really no big deal. I must have looked especially haggard because my enquiry sent the sweet barmaid into a near panicked flurry to find me lodging for the night. She seemed dubious of my claims that my tent would be adequate.

In Hawes, I set up camp at a small working farm campsite and dipped into town for dinner. On my way back, I discovered another backpacker, clearly exhausted, standing awkwardly at the driveway into the farm. He was another American, the first I had encountered on the trail this trip.

George Bernard Shaw once mused that “The British and the Americans are two great peoples divided by a common tongue.” This is a truth I often experience after a few weeks alone in England. I find that I’m much more careful about my slang and perform exhausting linguistic acrobatics to make sure that I am not misunderstood by my English counterparts. Three sentences into a conversation with another American and my guard is down. It is such a relief.

Charlie, a fantasy author from Maine, was out on a summer long ramble through the UK. He was unsure of where to go next and was very grateful for suggestions. Over dinner, I suggested he hike into Swaledale and hike the rest of the Coast to Coast to Robinhood’s Bay. The next day I set off to Askrigg.

A few years ago while leading a group of Americans through the Dales on a 100 mile pub hike, we made some friends in the Crown Inn in Askrigg. It was nearly 11pm and we were all sufficiently socially lubricated. With a glint in his eyes, one of the older chaps, after learning of our interest in pubs, began to tell of a pub a mile away. “Have you heard of the Victoria Arms in Worton? You don’t want to go there. Well maybe you do. If you do, don’t drink the beer or sit under the fox’s arse.”

A few minutes later, we found ourselves stumbling headlong into the pitch black country lanes towards Worton. We had no idea of the circus that was in store for us. When we arrived, the ramshackle pub looked closed but a little jiggle of door revealed a dimly lit and smoke filled old pub. Neil, the publican, is infamous in the Dales. He took over the pub when his father died years past. He is a part time farmer and full time renegade. The Victoria Arms stands in defiance to all modern pub trends and, for that matter, health codes. “I wear me wellies in the pub,” drunkenly sweeping his arms towards his footwear in a flourish “because of all the dog shite in the pub.” The rest of that night was a blur of pouring our own drinks and parlour tricks (which included getting wet from a suspect liquid ejected out of a stuffed fox’s hindquarters). It was one of the best times I’ve ever spent in a pub.

Back in 2021, I waited for the sun to set. Truth be told, I was reluctant to go back to the Victoria. I had too much fun the first time and I worried that another visit would marr the pub’s fabled reputation I built up in my mind. After an enchanting dusk walk through the picture perfect sheep fields of Wensleydale, I arrived at a now dark Victoria Arms.

Monday night. Chances were slim that this sleepy little pub was open. I heard music but barely saw any light. The door was locked so I gave it a knock. Moments later, a visibly less drunk Neil opened the door. “Can I get beer?” “Yes, come in.”

The first thing I noticed was a missing settle. A settle is an old English style of high backed wooden bench often found in older pubs. On my last visit I was enamored with the settle because of a mouse carved out of the arm rest. Not just any mouse, a genuine Mouseman of Kilburn mouse. These wooden mice can be found in the odd corners of North Yorkshire, the remnant of a whimsical long dead local artist. Neil explained that he sold the settle to the coal man who he owed money for said coal.

The second thing I noticed in the Victoria was a stack of porn DVDs sitting on a stool.

And here it is. We have the essence of what makes the Victoria Arms such a special place. Neil is the steward of a shrine. An unintentional museum of a nearly disappeared pub culture. Of course, porn dvds are not any part of pub culture but Neil’s unrepentant bucking of the system, his pure sovereignty over his domain and his unwillingness to give into making the Victoria Arms anything other than what it’s been for the last 100 years, couldn’t be further from the crass commercialism of the PubCos.

On one of the old white plaster walls hangs a painting of Neil’s father. The father lounges in his chair in front of a roaring fireplace. A lamb asleep on a blanket warming by the fire. The absolute pure picture of 19th century bucolic Yorkshire. Now step back and look. It’s nearly all there. Unmoved, untouched, probably undusted. His father’s chair. The fireplace, complete with nearly every single piece of ancient iron cookware. The taxidermied heads of animals, still in the same order. The lamb is gone but the publican – the mirror image of his predecessor- sits. Neil and I talk for nearly three hours. I encourage him to archive his memories of the pubs and his wonderfully entertaining misdeeds. He is sad about the settle and so I am.

It was midnight. I took the long way back to Askrigg, a mixture of elation and melancholy broadcast my gravely crunching staccato steps through the chilly August night.

The next morning I left Wensleydale for Swaledale. I made my way to Punchbowl Inn and then the Kings Arms. Both of which I expected to be closed on Tuesdays. To my surprise, they were open and packed. Poor planning resulted in missing lunch, so I set off along the Swale Way from Gunnerside to Muker with a belly devoid of food but full of Old Peculier.

I love Swaledale. I love the Swale. The narrow emerald grass pastures that flank the river. I hiked barefoot, something I’ve done along the Swale for years but nowhere else. If Yorkshire is God’s own county, the Dales is his temple and Swaledale is the holy of holies. I feel more me along that river than anywhere else in the world.

And my favorite village in Swaledale is Muker. Entering Muker, I made a beeline for the Farmers Arms, hoping to catch an early meal or at least get a table booked. Unfortunately, the pub was closed due to a health emergency. Even more unfortunate, there wasn’t a restaurant open on a Tuesday for a few miles.

With the prospect of missing out on lunch and dinner, I made my way to the campsite in Muker, relieved to discover they had a little camp store with enough provisions to make a respectable meal. In addition to the food, I decided to treat myself to a campfire. I bought some wood and a fire pit, pitched my tent by the river and watched the sun slowly – ever so slowly – set behind Kisdon hill. Just before the light completely faded, I was delighted to see American Charlie walking into the campsite.

Charlie and I had a nice night around the fire. He expressed interest in joining me up at Tan Hill the following night. However, while packing our tents in the morning, Charlie was worried about the wind forecast and camping on the exposed moor. Fortunately, I had already booked a room with two beds.

I tend to hike pretty fast, so I left Charlie back in Muker as I made my way to Keld and then up to Tan Hill. Tan Hill is the only building on an otherwise completely desolate moor. At one time the inn boasted that it was the highest pub by altitude in the world but I’ve noticed they’ve since toned down the claim to highest inn in Britain.

Tan Hill is a good pub. A very nice beer selection set in an exceptional rustic and old stone fireplace, complete with fires. Exceptional hearty food. The weather is nearly always bleak there, which makes the interior of the pub all the more inviting. The magic of Tan Hill is the fact that by 10pm all the people still in the pub are staying at the inn or in a caravan park outside. The result is a crowd of individuals that came to an isolated pub precisely to stay up and drink late. By 10pm a predictable ritual begins to play out. People start talking to others sitting at neighboring tables. Someone picks up a guitar or plunks out a twanging tune on the profoundly out-of-tune piano.

And so it was this night. After checking in, I came down into the pub to see a familiar face. The academic from Orton sat with two other academics. I went over and said hi. Charlie showed up and we had dinner. After dinner, the dance began. I started up a conversation with some hikers. We talked about the Pennine Way and LeJog. Before I knew it, a career army chap sat down. He was about to retire after 26 years, And then, the academics joined in.

And in a blur, before I knew it, we were all swept up into another room where a guest had found a guitar and was leading the rest of the bar in a 2-hour sing-along. Two young homeless looking 20-year-olds who were on the C2C sat down at the piano and pecked out songs from a dogeared pop music songbook. It was not very good but it was all fun and often hilarious. We banged our pints on the table, yelled out lyrics and were eventually told it was time to be quiet.

This was my third time to Tan Hill and I’m convinced a version of this plays out more nights than not. Tan Hill is a great pub because of it.

On OS map, there is a footpath from Tan Hill over the moors towards Reeth. The last time I was there, I was leading a group and fully intended to find the footpath but the weather was too miserable to subject the whole group to a muddy slog so we opted for the road. This time I was determined to find the footpath. Charlie was going to go a different route to Reeth. The two hobo 20 year olds said they were going to try the same path as me.

I set out first, and followed a track until it was clear that I was getting away from the footpath. Trusting my GPS, I set off over the rough in search of the footpath. Occasionally, I found something that might be considered a trail but for the most part, I was traversing over open country: bogs, full grown heather, ravines. It was a mess. My feet were drenched immediately.

At one point I found a segment of the trail and just as quickly as I found it, it melted away. After an hour and half of rough slogging, I came to a track that led out of the moor. I took it, convinced the footpath was long gone. Changed my socks and walked on the road towards Reeth. I will never try to find that path again.

After a few hours and a couple pubs, I landed in Reeth. I’ve been to Reeth many times. Truth be told, up until that night I didn’t really like the town. I’ve never been able to find a good time there. The locals seem distant and cold, perhaps exhausted by the never-ending parade of Coast to Coast hikers that stream through.

I pitched my tent, walked to nearby Grinton for an early meal at the Bridge Inn. I recently discovered that I have an ancestor from Grinton, so after dinner, I meandered through the church graveyard to say hi to my people.

I met Charlie. He needed to eat so we tried Reeth. There are three pubs in Reeth. One was completely shut due to staff shortages and the other two, next door to each other, were fully booked. The Black Bull, however, was offering a simple pie meal to anyone who needed a meal and was willing to eat in the bar. This impressed me. In the well over 80 pubs I’d been to on this trip, this was the first one that found a way to accommodate people who could not book a table for one reason or another. It was simple food but hot and hearty.

As Charlie was finishing up. The hobos stumbled in looking worse for wear. It turns out they had endured the nonexistent moor footpath further than I. As a result, they spent the entire day on the moor. When they finally found a way out, a couple of farmers took pity on them and drove them to the Black Bull. I bought a round.

The young hobos’ names were Hector and Felix. They were not homeless, just road weary. Both were very intelligent, kind and curious. One was in his third year of medical school. They loved music and impressed me with the breadth of their musical tastes and knowledge.

The Black Bull is a solid pub. It’s the only place in Reeth that has tequila. On previous trips to the pub, I was amused by the overly terse woman behind the bar. A truly sour person. The caricature of some old barmaid. She was not there that night but when I asked the bartender about the grumpy bartender, he blurted out her name before I finished my sentence. We both laughed.

Besides tequila, the Black Bull has another rare pub delight: a game room with a jukebox. I feel like at this point that I can say with authority, it’s the only jukebox in a Yorkshire Dales National Park pub.

We played pool and fed pounds into the jukebox. It was raining and about midnight, Hector and Felix began to talk about where they were going to camp. Young as they were, they didn’t have the funds for a campground let alone a room anywhere. At Tan Hill, I found them huddled under a rock face in the morning. After the shitty day they had, they were not looking forward to finding a campsite. The landlady had recently joined us and mentioned they had a room. I worked out a deal that if she could convince them the room was free, Charlie and I would pay for it on the sly. And so it was.

The immediate effect of the arrangement was to endear me to the landlady and her husband. The poor couple had bought into the pub 3 weeks before Covid hit. They’ve had a hell of a time. After they discovered what I was doing, they wanted to know how the Black Bull stacked up. I told them about how impressed I was with the pies and that no other pub was being so hospitable. The landlady beamed. It was her idea. She told me no less than three times.

I woke up on my last day ready to be done. On a whim, I made for a pub that appeared just outside the park boundaries. The Bolton Arms in Downholme. When I arrived, I realized the pub was actually on the opposite side of the street and was within the park boundary. I had probably the best sandwich of the trip: wonderfully crafted cumberland sausage and caramelized onions on a fresh baguette.

During my last three miles, I found my pace quickening to my favorite pub in the world. The George and Dragon in Hudswell is one of the friendliest pubs I’ve visited. It’s community owned and it shows in the locals’ love for the place. Their real ale selection is not just large, it’s very thoughtful. All the pulls are from smaller, more crafty local breweries. There’s always a couple darks on. When I was there, there was a mild, a brown and a porter. That’s just not common. The food is simple and delicious. Music played from records. A well tended coal fire.

The beer garden overlooks the last bit of the Yorkshire Dales. To the east, you can see the valley dissolve into flat farmland. You face north but in the summer you can watch the slow motion sunset behind the emerald green dale. It’s perfect.

Good beer? Check. Exceptional even. Vibe? Pure bucolic. Based on these two criteria, it is an exceptional pub. I’ve been to a number of community owned pubs. Usually, there’s a much warmer atmosphere in such pubs. The George and Dragon excels in warmth.

Despite the try-hard craft beer offerings, there’s no air of pretension. The publican is a soft spoken, jovial and hard working dude. I almost bumped into him as I crossed the threshold. “It is you! I saw the name Kevin on the booking sheet and asked if it was the American!” We laughed. He sat with me and Charlie (who met me in Richmond) for a pleasant chat. “We were sorry to miss you last summer.” “Not as much as I missed being here, Stu.”

The pub. It’s my favorite thing about England. All the things I love about a pub seem to be distilled in Yorkshire: tradition, love for real ale, community. I’ve hiked to all but one pub in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. I’ve traipsed through damn near every small and secret place. My brain tells me that I should move on to fresher adventures but I dream of the Dales. I can’t wait to go back. Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name.

My top 5:

George and Dragon, Hudswell

George Inn, Hubberholme

Craven Arms, Appletreewick

Victoria Arms, Worton

Tan Hill

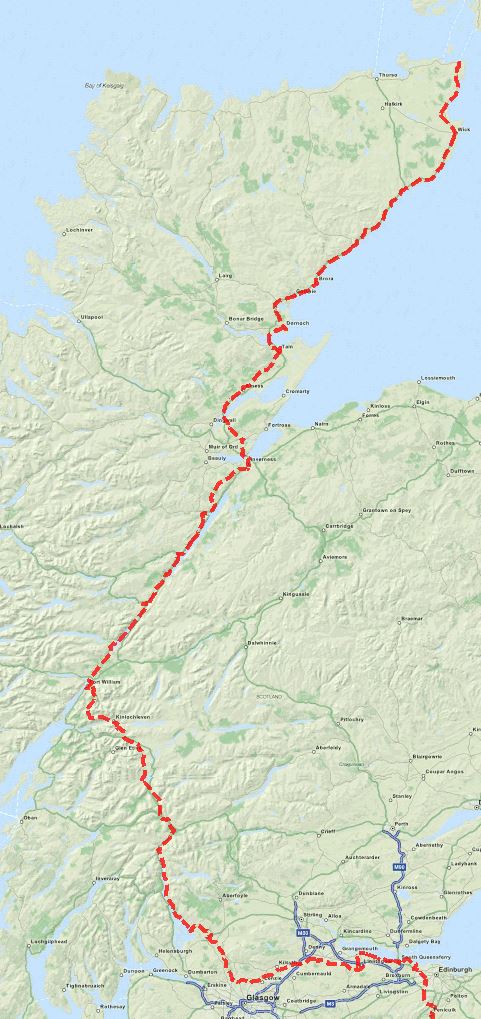

Rough sketches of my route